Early Contributors to the Science of Blood Culture

By the bioMérieux Editors | Reading time: 2 min

PUBLICATION DATE : OCTOBER 31, 2022

October is associated with Halloween, a day known for ghosts, vampires, and ghouls. This October, the Living Diagnostics blog highlights an ominous-sounding—but absolutely critical—step in infectious disease management: blood culture. Today, blood cultures are a commonplace, highly advanced, and often automated function in microbiology laboratories, but this was not always the case. So, we are taking this opportunity to highlight three scientists whose research was integral to the blood cultures that laboratory professionals now regularly perform.

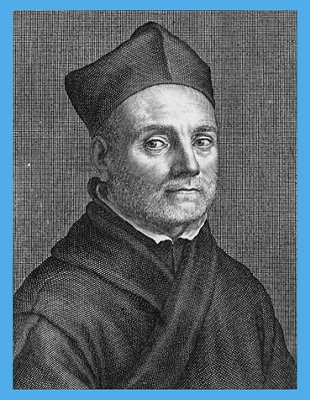

Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680)

Athanasius Kircher was a German Jesuit scholar who played an early and important role in the detection of microorganisms in blood. Kircher is referred to as a “polymath,” meaning someone whose knowledge spans numerous, complex subjects, and he took an interest in not only medicine but also geology and linguistic studies. During the plague epidemic in Italy in the mid-1600s, Kircher used an early microscope to study the blood of plague victims. He described seeing tiny worms in the “verminous blood of fever patients,” concluding that the disease was caused by microorganisms invisible to the unaided eye.

However, the microscope he used would not have been capable of seeing the microorganism responsible for the plague, Yersinia pestis, and it is more likely that he observed clumps of red or white blood cells. Kircher’s work was critical to the development of blood cultures as we know them today, as he pioneered our understanding of the concept of finding microorganisms in blood.

Athanasius Kircher . Cornelis Bloemaert, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Athanasius Kircher . Cornelis Bloemaert, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

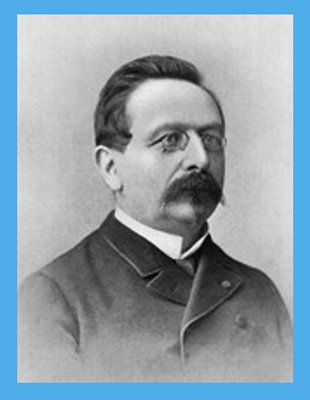

Dr. Jean-Antoine Villemin (1827-1892)

Dr. Jean-Antoine Villemin, a French physician, is remembered for the critical role he played in our understanding of infectious diseases. Dr. Villemin showed that tuberculosis is an infectious disease by inoculating laboratory animals (such as rabbits) with blood, sputum, or other materials from humans or animals with tuberculosis, and observing that the laboratory animals developed lesions indistinguishable from those produced from the original infection in the human patient.

Though Dr. Villemin’s work was largely ignored at the time of his discoveries, in 1893 he posthumously received the Prix Leconte, which is a prize that was created by the French Academy of Sciences in 1886 to recognize important discoveries in scientific fields, and it is still awarded today. Dr. Villemin’s work improved the scientific community’s understanding of how blood is able to harbor infection-causing microorganisms, which is a concept central to why blood cultures are performed.

Dr Jean-Antoine Villemin. Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Dr Jean-Antoine Villemin. Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

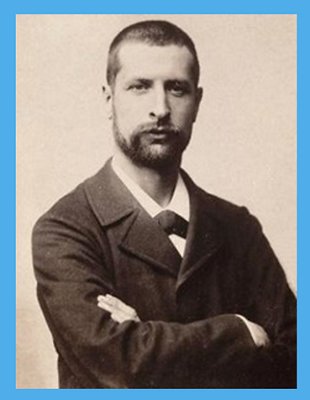

Dr. Alexandre Yersin (1863-1943)

Alexandre Yersin, a Swiss-French physician and bacteriologist, also received the Prix Leconte. Yersin studied at Louis Pasteur’s research laboratory at the École Normale Supérieure, and later joined the Institut Pasteur, where Marcel Mérieux, patriarch of the Mérieux family that founded the Institut Mérieux, also worked. Yersin is recognized as a co-discoverer of the bacillus responsible for the plague, which was named is his honor—Yersinia pestis. If that microorganism name sounds familiar, that is because Yersinia pestis is the microorganism that Athanasius Kircher believed he found under a microscope over 200 years earlier.

There are few infectious diseases that strike fear in the heart the way that the plague does, and Yersin’s work in studying bloodborne pathogens highlights the importance of blood cultures as a means to grow and then identify microorganisms in the blood. Though they lived two hundred years apart, Kircher and Yersin’s work are intimately connected, which shows—at the microorganism level—the importance of building upon previous scientific discoveries for the greater good.

Dr Alexandre Yersin. Musée d’Orsay, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Dr Alexandre Yersin. Musée d’Orsay, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

SHARE THIS:

- Infectious Diseases

< SWIPE FOR MORE ARTICLES >